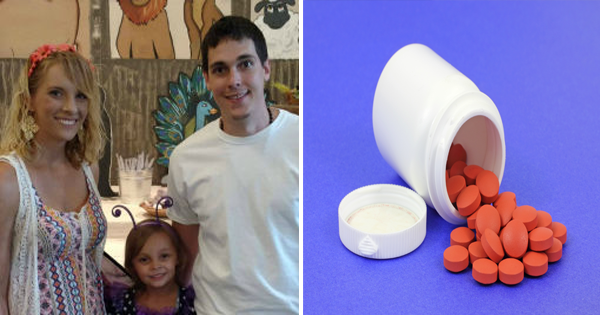

Amanda Fink was first introduced to prescription medication abuse when she was a little girl, growing up with her mom. “When I was upset,” Fink recalled, “[My mom would] give me [a pill of Oxycontin] and say, ‘Here, this will make you happier.” Her mother had been prescribed Oxycontin after a hysterectomy left her with scar tissue.

Now 28 years old and a mother herself, Fink finds herself in her mother’s shoes.

When Fink gave birth to her daughter three years ago, she immediately received her own prescription of Oxycontin. Her nerves had gone so high during labor that even after her daughter was born, Fink’s doctors continued to prescribe her Vicodin.

It only took Fink a few months to become addicted. She began to take Vicodin to ease her postpartum anxiety, and when that was no longer enough, she turned to heroin.

Unfortunately, Fink’s gradual decline into addiction and reliance on painkillers isn’t unique, especially not for new mothers.

Painkiller prescriptions and sales have gone up fourfold in the past 16 years, and in 2012, enough prescriptions were written that every adult in America would have had access to their own, individual bottle. This growing problem is also incredibly hard to define; the demographics of a pain killer addict span across all genders, races, and socioeconomic statuses.

For mothers like Fink, it seems natural to turn Vicodin to ease the bore of social obligations, like family parties, and justify taking it. “I always felt like, it’s just a pill,” Fink admitted. “This is something FDA approved. Doctors prescribe them.”

But just as it was all too simple to take Vicodin on more and more separate occasions, it was also too easy to become addicted to the substance without realizing it.

“The first time I ever felt withdrawal, I didn't know it was withdrawal,” Fink recalled. “I went to my doctor and told him I was having nausea. He wrote me a prescription for Klonopin and just said, 'Whenever you feel nausea, just take this.' I had no idea that was addictive too. I just wanted some help for my stomach."

When Fink finally realized that she was addicted to her prescriptions, she called a Suboxone clinic to get help – which was much harder to come by than her pills. "You can be a drug addict and call a Suboxone clinic and say you want to quit, and they say they can't get you in for two months,” Fink said. “Well, what do you expect me to do in two months? Die?"

She eventually took matters into her own hands by easing herself off the medication by substituting it with sleeping pills as her parents helped take care of her daughter.

Fink is now safely off the pill and much better – physically and mentally – than before, but she can’t imagine needing to tell her daughter the truth of her past.

"I'm hoping that no matter how I tell her, she doesn't hate me for it," Fink said, “if she goes to a party and there are drugs there, I want her to have the tools she needs so she won't fall into that."