When Charlotte Hilton Andersen received an email from her second son’s fourth grade teacher, of which the subject line read, “We need to talk,” she knew there would be no good news following.

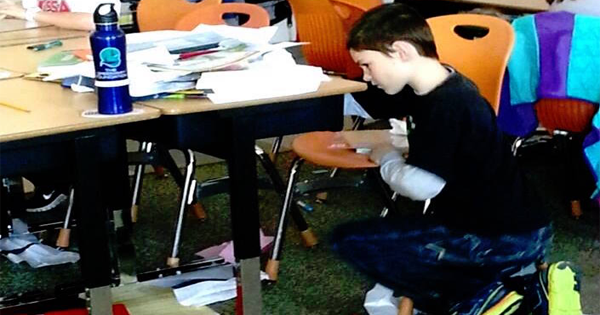

Once Andersen opened the email, she read that her son “moved to doing his work on the floor because his desk [was] so messy he [couldn’t] sit on it, much less use it. This needs to change.”

Accompanying this blunt message was also this photo:

Andersen’s first reaction was to fly to her son’s defense – but even she knew that her son’s behavior needed to change. She’d spent his entire life trying to discipline him enough to clean, to sit still even, but he seemed constantly oblivious to the real world.

After Andersen received the email, she brought her son to the doctor where he was diagnosed with Attention Deficit Disorder (ADD). It was a diagnosis that had been predicted, diagnosed, and medicated by his teacher, pediatrician, and psychiatrist.

Initially, Andersen refused to have her son take ADHD medication; she wanted to discipline her son and change his behavior herself.

But when Andersen’s son failed to exhibit any changes, his doctor asked, “Why not just try the meds? It can’t hurt and will probably help.”

The doctor’s advice couldn’t have been more wrong.

Andersen’s son was more able to sit still at his desk, finish his homework, and stay seated during class – but he was doing all of that to spend more time focusing on the wrong things. In other words, the medication was improving his focus on the fantasy world inside his own head, not the world around him.

This wasn’t the only strange behavior he displayed. Andersen’s son was also suddenly craving grapefruit, and only on days that he took the medication. These cravings only got worse and worse as time passed. Some days, he would eat eight grapefruits, and nothing else.

Andersen watched her son become emaciated and knew – she had to take him off the medication.

The doctors didn’t support Andersen’s decision, but at that point, she was just desperate for her son to resume his normal eating habits again.

Immediately after Andersen took her son off ADHD medication, she sent him into a behavioral modification therapy program specifically for children with ADHD, and after a year, he’s doing better than ever.

Andersen and her son’s story is, unfortunately, just another indication that doctors prescribe medication that don’t necessarily benefit patients and don’t always have to be used to improve a situation.